I originally posted this rather long thread on Twitter. If you think it too long to read, the summary is that reversing QE could be the recipe for an absolute economic disaster.

All the debt issues by the government to pay for Covid – about £450 billion of it – was in effect bought by the Bank of England. The government owns the Bank of England. So Covid debt is owed by the government to itself. Why do we have to repay it then?

Covid cost the UK around £450 billion. It so happens that since March 2020 the Bank of England has bought that same value of government bonds. All were issued to pay for Covid. In other words, neither taxpayers or financial markets have paid for Covid. The Bank of England did.

The Bank did that by creating new money. There is nothing magic about this. Every time a bank lends money, even when you use your credit card, new money is created. You promise to pay the bank and they promise to pay whoever you want. And those two promises create new money.

Money is just debt. It is a promise to pay. That is all. When Covid began promises to pay were in short supply. People stopped spending. Banks stopped lending. Work closed down for many. The government knew money might stop being made. So they stepped in and started making it.

Under international regulation a government is not meant to borrow from its central bank – in the UK’S case the Bank of England. So, instead, they have to do this in a roundabout way. The government issues bonds to fund its debt and the Bank of England buys them.

To make this purchase possible the Bank of England has to create the money. It can’t lend it direct to the government. It can’t lend it to itself. There is no promise to pay in that case. So it created a new company owned by the Bank to lend the money to.

This company was and is called the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited. Call it the APF, for short. The APF borrowed money from the Bank of England to buy the bonds the Treasury was issuing. It promised to repay the Bank.

There was, however, a twist to the tale. In case the APF could not for any reason repay the Bank of England, the Treasury – which is the finance division of the government – guaranteed to pay the debt on its behalf. So, in effect, the government did borrow from the Bank.

How can I be so sure that the government borrowed from the Bank of England? Simply because if all money is debt created by promises to pay then it was the promise of the Treasury to repay the money borrowed by the APF that made this process possible.

This process was and is called quantitative easing. It looks and is technical. The essence is, however, incredibly simple. The bonds issued by the Treasury are bought by a company technically owned by the Bank of England using a loan guaranteed by the Treasury. That’s it.

The consequence of quantitative easing, or QE for short, is in that case that the Treasury owes the Bank of England for the money that the Bank creates that the government can spend.

And the government did, of course, spend. It spent around £450 billion of Bank of England created money on furlough, supporting business and the self-employed, and PPE. In other words, the money the government created using QE was spent into the real economy.

It’s important to understand how this money got into the real economy. The process is, as usual, simple, but little understood. The money goes from the Bank of England to the person due it – such as a person receiving support as a self-employed person – via a commercial bank.

The Bank of England did not pay the self-employed person directly. The Bank paid HM Revenue & Customs’ commercial bank account. That commercial bank account then paid the self-employed person. The QE created money, made by a Treasury guaranteed loan, was now in the real economy.

There is an important element in this most people don’t get. The commercial bank paid the self-employed person because HMRC asked it to. And it did so because the Bank of England credited it with the money to do so.

But remember, money is not real, or physical. It is just a promise to pay. What the numbers that represent the balances on your bank account mean are that you have either promised to pay the bank if you are overdrawn, or they have promised to repay you if you are in credit.

That’s all those numbers in your statement mean. There is nothing you can see, touch or feel that looks like money that those numbers represent. They are just numbers. They are simply the amount of debt owing between you that one has promised to pay the other.

I sort of hate to break this to you if you have never appreciated it before, but there is no ‘money in the bank’. There is just a computer that records debts owing to and from people. That’s it. That’s all a bank is. It’s an accounting system to record debts owing.

That’s important. It explains why when the Bank of England credits commercial banks with money to pay for government spending the debt that the Bank of England owes to the commercial bank – like HSBC – does not disappear when the self-employed person is paid.

The commercial bank pays the self-employed person as instructed, by increasing their bank account and reducing the account of the government department that made the payment. But, the government department got its funds from the Bank of England in the first place.

That sum owing from the Bank of England to the commercial bank is not then cancelled by the payment made to the person eventually owed money. The government still owes the commercial bank.

Only, we don’t actually describe it like that, because what’s actually recorded is that the commercial bank has money on deposit with the Bank of England as a result of this transaction.

Bank deposit accounts are, of course, just money owed by a bank (in this case, the Bank of England) to whomsoever has deposited money with them. But in this case there is something special about the deposit. The Bank of England deliberately made that money.

All banks can create money. I have already noted how. They just record promises to pay. But the government and Bank of England create a special form of money. It’s called base money.

Some of this base money is the only type of money you can see, touch and feel. That’s because it is the notes and coins that we use. There are around £80 billion worth of these in circulation right now. But don’t get confused. They too record a promise to pay. They aren’t money as such.

If you are in doubt about the fact that notes and coin just record promises to pay think what happens when it is said that a note or coin is being taken out of use. Suddenly we want to be rid of them. That’s because they are no longer of use in recording or cancelling debts.

So, notes and coins only differ from the rest of money by recording debts owing and settled in a physical format rather than through a computer screen. Think of them as being like an abacus in that case, instead of being electronic.

Now let’s get to the more important form of base money. This is the electronic money that that Bank of England has been injecting into the economy in large amounts since 2009.

When the Bank injects new money into the banking system it does so via what are called the central bank reserve accounts that the commercial banks maintain with it. I stress, you can only have such an account if you are a commercial bank or financial institution.

These central bank reserve accounts are the way money flows from commercial banks to the Bank of England. They are, for example, the accounts used by the commercial bank you pay tax to if you are a company, self-employed or an employer for them to then pass it to the government.

These central bank reserve accounts are also the way in which the commercial bank accounts of government departments are topped up when required to ensure they can make payments to whomsoever is due money. The Bank of England then makes payment to those commercial bank accounts.

Vitally, they are also the way in which the proceeds and sales of government bond (or gilt) issues flow to and from government. So, if the government sells bonds money flows from the commercial banks to the Bank of England to reflect what people pay for those bonds.

Similarly, when the government repays a bond at the end of its life (and all gilts have a fixed life now) then these accounts are used to repay the funds owing. The government pays the commercial bank via its central bank reserve account and they then pay the bond holder.

I know this is getting a bit technical but stick with me, because the next bit is important. A vital thing to understand is that we have had two quite distinctly different eras of quantitative easing since 2009.

The first QE era was from 2009 to 2016. The aim at this time was firstly to inject new money, or liquidity, into the banks so that they could not fail again. The second aim was to keep interest rates as low as possible. The third aim was to encourage riskier lending by banks.

These need brief explanation. The injection of new money into the banks was necessary because from 2008 onwards the commercial banks stopped trusting each other. They realised that they had all been reckless and had piled their balance sheets high with useless loans.

What they also realised was that which bank might fail next was unknown. Remember that many did fail and were bailed out by the government. What the remaining banks realised was that they could not trust each other. Any of them might go bust at any time.

What this meant was that they would not accept each other’s promise to pay. But, banks paying each other is vital. It’s how a payment from an account held at Lloyd’s gets into another account paid at Barclays, for example. Unless banks pay each other the system fails.

So, an alternative to the banks simply trusting exchange other to pay – which was the arrangement used before 2008 – had to be found. That alternative was to use the central bank reserve accounts for this purpose – because money held with the government was always reliable.

All the commercial banks knew that the money that they held on deposit with the Bank of England was guaranteed because the Bank of England can never go bust. After all, the government can always create new money to make any payment, if it wants.

So, the central bank reserve accounts are the sole source of cast iron, guaranteed to pay, money that there is. And for that reason the accounts that record the commercial banks’ stores of this money have also been used post 2008 to make payment between commercial banks.

It’s a weird arrangement. The overall balances on these accounts are decided by government. It decides how much it wants to pay into and withdraw from the economy, and that determines the account balances. So the banks get this money whether they like it or not.

If ever there was a magic money tree this is it. Hundreds of billions of pounds is now held in these accounts, essentially gifted to the commercial banks by the government but which the banks can’t withdraw without government permission or use for anything but paying each other.

The trouble was that in 2008 there was only £42 billion held in these accounts. If they were to be used for more than payment to and from government then bigger balances were needed to make sure no commercial bank went overdrawn.

QE created those bigger balances. The government bought its own debt. The commercial banks’ central bank reserve accounts were credited for those payments. The amount available for the commercial banks to pay each other increased. This is how those commercial banks were bailed out.

The process had two other consequences. First, buying £450 billion of government bonds in this way kept the price of those bonds high. And since bonds carry a fixed interest rate for their whole life a bond with a higher price has a lower implied effective interest rate.

This is how the low interest rates since 2009 were forced upon the financial markets. It wasn’t just because the Bank of England paid low rates. It reinforced its policy with about £450 billion of bond purchases.

The Bank hoped that because it only paid minimal interest on this sum the commercial banks would be encouraged to increase their lending to high-risk businesses. That did not happen. They increased mortgage lending and financial speculation instead.

The result of the Bank of England failing to understand what would happen with QE was that we have had a house price boom and massive increases in share and other asset prices. The rich just got richer. This was how the finance sector and landlords were bailed out by QE.

Excepting the fact that our remaining banks survived and another crash was avoided, the version of QE used from 2009 to 2016 was a disaster for the UK economy. It created asset price inflation, kept wages low and increased inequality.

In that case let’s be clear that the type of QE used since March 2020 has not been the same as that used from 2009 to 2016. I stress that the Bank of England would like you to think that it is, but it is not. Their clams about this are not true.

What we known is that in the spring of 2020 the Bank of England agreed that in the face of a looming crisis that they would fund the UK government to keep it going. We know that is true. The FT reported it:

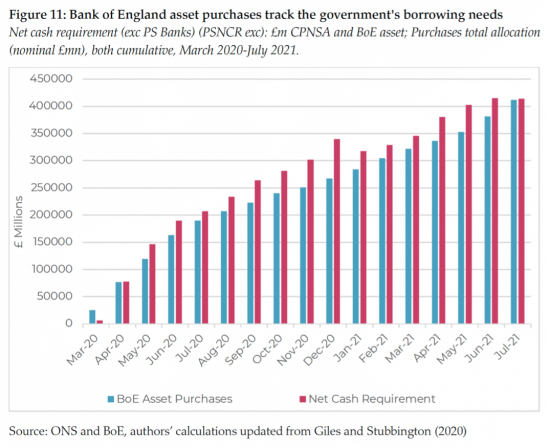

And this is what they did throughout 2020 and 2021. This chart from the @NEF shows what happened:

Every time the government spent money the Bank of England undertook QE to match, with very small lags between the two. The process used to undertake this QE looked similar to that used from 2009 to 2016. Government bonds in issue were repurchased.

However, this time, in effect, happened was that every time new bonds were issued as a result of government spending taking place without tax revenues to match the Bank of England stepped in and effectively bought bonds of a similar value to those just issued.

Although the bonds issued and reacquired may not have been the same – and they were not, always – the process was one that guaranteed that no real funding from the bond market was asked for. Instead the Bank of England provided all the funding the Treasury needed.

The impact of QE on the central bank reserve accounts was quite different as a result. From 2009 to 2016 when QE took place there was no immediate match with government spending and the bonds purchased had usually been in issue for some time.

The result was that from 2009 to 2016 QE lifted the value of the central bank reserve accounts by an amount that over time broadly equalled the amount of QE. I stress that the relationship was not precise, but this was very clearly what happened.

From 2020 onwards that was not what happened. Every time the government was at risk of spending more than it was raising in tax revenues it issued bonds. Issuing bonds reduces the balances on the central bank reserve accounts.

But then, usually at around the same time and often within days of it, the Bank of England bought bonds back from the financial markets. What this meant was that the central bank reserve accounts were restored to their original balances.

As the New Economics Foundation chart shows, these transactions almost exactly matched each other. The result is that this QE could not have increased the balances on the central bank reserve accounts held by the commercial banks.

What we do know, however, is that those balances rose. In February 2020 they stood at £479 billion on the Bank of England balance sheet. A year later they stood at £803 billion. The increase might have looked like the increase in QE in this period, but it can’t be.

For the reasons already noted, QE could not have increased the central bank reserve account balances during this period. There was no new debt issued to or withdrawn from financial markets to make this happen during that period. So, we must be seeing something else.

We are. As the Bank of England said it would in April 2020, it was directly funding the Treasury. That is what was happening. QE operations over the last two years were little more than an a set of sham transactions intended, as ever with QE, to disguise what was really happening.

In this case the reality is that nothing has really happened in the bond market over the last two years. In March 2020 according to the Debt Management Office of HM Treasury the market value of government debt in issue was £2,219bn and 23.4% was owned by the government.

In September 2021 (the most recent data available) the market value of all gilts was £2,589bn and 33% was owned by the Treasury. Ignoring Treasury ownership debt was, then largely unchanged from £1,699bn net of government holdings in March 2020 to £1,734bn in September 2021.

So, given that QE operations take place at market rates QE is not changing the central bank reserve accounts. In that case the something that is changing them is the Bank of England simply injecting the money it creates into the economy. That is what has happened since March 2020.

To date more than £400 billion has been spent in this way. This has enormous implications. First, it says that the whole game of QE has been a charade, knowingly played by the Bank of England.

Second, it says, more importantly, that the supposed debt owing has nothing to do with the bonds supposedly issues during the course of the Covid crisis. Although by September 2021 there were supposedly £2,023 of these in issue, precisely one third were owned by the government.

As the analysis noted above implies, this means that in real terms there was no new actual debt owing by the government during this period, at all.

So, that’s where we are. Although the government claims it has issued a pile of debt that it says we cannot afford now to pay for Covid that is not true. One third of that debt is already owned by the government and so is already cancelled, in effect. And real debt has not risen.

On the remaining net debt interest rates to be paid are at record low levels, and that will remain true even if the Bank of England increases rates (as the government, bizarrely, wants it to do) over coming months.

But, publicly unacknowledged by the government and the Office for National Statistics, is the reality that the amount of money held by commercial banks on deposit with the Bank of England has increased to around £900bn, up from £42bn in 2009.

Now the government is ending QE. But is is going to run a deficit of almost £100bn next year. So it intends to issue bond of that amount. And it is stopping reinvesting the value of QE bonds when they are repaid at the end of their lives. That sum may be £25bn next year.

In other words in the next year the government will ask for around £120bn from the financial markets when it has been asking for nothing of late. Let’s put this in context. It’s almost the amount paid in VAT each year. It’s £20bn more than we spend on education.

If income tax was to be adjusted to take this sum out of the economy the basic rate of income tax would have to double from 20p in the pound to 40p in the pound. That’s how big this change is. That is what the government is planning to take out of the economy in the coming year.

The central bank reserve accounts which guarantee the safety of our banks will fall in value. Pension funds, banks, life assurance funds and others will have to find the money to buy these government bonds.

And the government is planning to increase interest rates to make the bonds, which they do not need to sell as they could do more QE instead, attractive to purchasers. So, selling these bonds has a massive real cost impact for UK households.

Let’s be clear that some households will go bankrupt or lose their homes as a result of these bond sales and the resulting interest rate rises, which will push interest rates on mortgages up.

But that is not the end of the chaos that I fear. I think the Bank of England has got this policy horribly wrong. They think that there will be no disruption in financial markets as a result of this change of plan from the Bank. I think they are wrong.

We know that share prices are historically very high. Right now the UK stock market is valued at more than thirty times the annual earnings of the companies quoted on it. Historically a rate of around fifteen times was considered fair.

In the US we have seen the threat of interest rates causing stock market mayhem before it has really happened. The value of Facebook fell $200bn in a day recently. January saw a big stock market fall in the US.

I think that as UK banks, pension funds and others begin to sell shares to buy government bonds we might see the same thing happening here. And net selling stock markets in shares can be chaotic, and even panicky.

Stock markets are good at putting prices up. They are really bad at the downside. Stock markets don’t usually descend gently, which is what the Bank of England policy demands. They tend to crash.

If at the same time banks are pushed for money as the Bank of England takes £120 billion out of the economy and the banks react by reducing mortgage lending we could see a reverse in house prices as mortgages get more difficult to get.

Perversely, this might have another consequence. To get higher interest rates on bonds the Bank of England hopes bond prices will fall, which is logical as they will be making more of them available to financial markets. But that may not happen.

When financial markets become chaotic savers tend to flock to safety. Government bonds are the safest savings account anyone can get as the UK government cannot go bust. What that means is that demand for bonds might increase by more than the amount the government wants to sell.

Perversely, what the government is planning may backfire then. So big is the demand for money it plans to make in the next year the likelihood exists that it could create market chaos and crash share prices, and increase the price of bonds so for that interest rates go down.

If this happens not only does government policy fail, but we get a crash and massive household stress all because the Bank of England wants to reverse QE, much of which was never real in the first place as it simply provided cover for direct government borrowing from the Bank.

And, remember, that even if none of this happens a sum equivalent to education spending is being taken out of the economy. That is going to have a big knock on effect, equivalent to a big tax increase. That’s enough to create a recession in itself.

So why is the Bank so desperate to reverse QE then? First, that may be because it believes its own claims that it did not fund the government, but just kept interest rates low by doing QE and now wants those rates increased to help tackle inflation.

That is perverse of course. Thinking that increasing or inflating the price of money is going to control inflation was always perverse.

Second, it may believe the figures for government debt that ignore the fact that it owns one third of that debt. Perversely, it seems to think reversing QE will reduce debt. But to achieve that they are actually increasing the debt. You could not make this up….

Third, they want to do this just because they can. They don’t like it being said that they funded the government for the last two years and so they are trying to prove they did not by being macho now. They are playing games.

But, the price of those games could be catastrophic. We already have a cost of living crisis that the government is making worse by perversely increasing taxes. Now we have the Bank wanting to destabilise the financial markets as well. They may also trigger a recession.

If the Bank is wrong and I am right (and we don’t know, but they are gambling more than I am) we get a crash at enormous cost to us all and all because of the Bank’s perverse logic that QE is ideologically wrong and must be reversed.

We cannot afford their ideological crisis right now. We need real world policy to deliver real world change. That would mean we would have to acknowledge how QE really works, and tackle the inequality side effects of it using tax.

We’d also need carefully planned policy, delivered through regulation and tax, to slowly deflate financial markets.

But what we do not need is a Bank of England and government-created crash that might result in mass hardship. There is, however, real risk that this is where we might be heading unless plans are changed. We have to hope that they are.

You can read more on this and other issues on my blog.